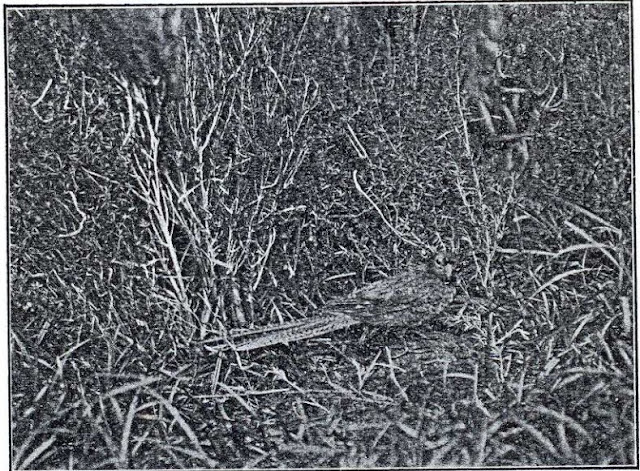

The photo within the article below could well be the first

photo of the Eastern Ground Parrot and is almost certainly the first published photo

of an adult bird taken in the wild.

Arthur Herbert Evelyn Mattingley was an enthusiastic amateur

ornithologist and a pioneer of bird photography. Born in Melbourne in 1870, he

was an inaugural member of the Royal Australasian Ornithologists’ Union, and a

founding member of the Bird Observers’ Club. His photos were pivotal in the

campaign to stop the slaughter of egrets for their plumes.

In the article below, his keen observation and enjoyment of

birds shines through. Mattingley would be pleasantly surprised to learn that the Ground Parrot, though endangered, can still be found in Victoria.

Mattingley,

A. H. E. (1918). The Ground-Parrot (Pezoporus formosus). Emu 17,

216-218.

The Ground-Parrot (Pezoporus formosus).

BY A. H. E. MATTINGLEY, C.M.Z.S.

The Ground-Parrot

Photo by A.H.E. Mattingley C.M.Z.S.

These beautiful birds are to be sought where the Wind goes

alternatively sobbing, soughing, whistling, and sighing through

the harsh herbage, which renders the bird’s light-timbred call

difficult of segregation. This separation from other bird calls

and subsequent fixture of the position of the Ground-Parrot’s

voice is a requisite essential to successful observation and the

discovery of the bird and its place of abode without its being

startled by being forced to fly up to disclose itself, which act is

contrary to its desire and usual habit of comporting itself.

This interesting bird is local in habit, and can usually be found

in the same area of country - moorlands or coastal plains. To

seek out a bird, one should requisition the services of a well-trained

pointer or setter, which can help one considerably to find and

flush the bird when desired, or to “ point ” it out. These birds

have a “ scent,” and dogs can readily “ pick up ” their trail, run

them down, and “ set” them. As they go singly or in pairs,

and are sparsely distributed, a dog that “ ranges ” well will soon

indicate their presence or absence.

In selecting its home, the Ground-Parrot naturally frequents

a type of country that affords a close covert as a protection from

observation from above, and in harmony with its own colour;

and as well it chooses a class of growth that permits of the free

exercise of its habit of running rapidly through it, but free from

observation; and a place which also contains its food supply,

consisting mainly of the seeds of grasses and shrubs and tender

shoots of plants.

The Ground-Parrot has been occasionally encountered in

swampy places on uplands, and has also been found on open

plains and swampy areas on mountains. Like its congener, the

Night-Parrot (Geopsittacus occidentalis), the Ground-Parrot is

doomed to early extinction on the mainland of Australia,

especially in those parts whereon the foxes are encroaching, in

the course of the next few years, as will be shown later on.

The call of the Ground-Parrot is issued in a somewhat warbling

fashion, harmonious withal, but conveying a sense of sadness

well befitting the nature of its environment. On windy days

the note is rarely heard, no doubt on account of its want of

fulness and carrying capacity. It appears to be used solely in

calling to its mate. As far as could be ascertained, it uses its

call as infrequently as possible. The following is the call set to

music, and is repeated softly by the bird two or three times

generally :—

The notes, therefore, of the last remnants of the Pezoporus are not

easily detected.

Ground-Parrots lead a terrestrial life solely, and are never found

in trees. 1 have seen a bird, however, climb up to the height

of about one foot on a shrub after some seeds growing thereon.

When flushed they fly rapidly away, somewhat after the whirring

manner of a Quail, but not so direct, since they zigzag in their

course. No fright screech is uttered either when rising from the

ground during flight or on capture. When handled, the birds

bite savagely in defence of their liberty. When flushed, they

mount up in the air about 4 or 5 feet—usually a foot or two above

the herbage—and proceed from 3o yards to even as far as

200 yards should the intervening ground flown over be too open

or otherwise unsuitable to alight on as a covert. The late Mr,

A. ]. North records that on one occasion he noticed birds that he

had flushed alight on a fence.

I am informed by an old Quail-shooter who lived by hunting

that his retriever dog used, years ago, when the Parrots were

plentiful, to run down these birds and frequently capture them.

This evidences the fact that it is a difficult matter to flush the

birds. I have noticed, once birds have been flushed, if there be

plenty of cover available, the Ground-Parrot will not flush again,

expose itself, and fly away, but it prefers to trust to its powers

of running to place itself beyond danger. They sleep on the

ground at night, and are therefore easily caught by prowling

foxes, since the strong scent emitted by them attracts the wily

animal. As they nest on the ground, the fox and other predatory

creatures, such as domestic cats gone wild, dingoes, native cats,

snakes, and lizards have little difficulty in obtaining their eggs

or young.

An old correspondent of mine, Mr. Percy Peir, a well-known

aviculturist, of Sydney, has kept a pair of these Parrots alive for

some years in an aviary where the conditions were more suitable

than in the ordinary bird-cage, and where they could run about

on the ground.

Ground-Parrots are exceedingly active and graceful in contour,

and the colour of their plumage is as distinctive as the livery of

many other Australian Parrots is gaudy. The adult plumage of

both sexes is similar, being dark grass-green, or, to be more

correct, a bright Rinnemann’s green, barred alternately with

black and yellow, on the upper surface, and a yellowish~green,

barred also alternately with black and yellow, on the lower and

abdominal surfaces. The forehead is surmounted with a distinct

scarlet-tinged nopal red patch. The feet (which are somewhat

large, and have four toes) and legs, adapted for running, are of a

fleshy-pink colour tinged with blue-black.*

Their food consists largely of grass seed, such as that of

kangaroo-grass (Anthistiria), fruit of the tea-tree (Melaleuca),

wattle (Acacia) seed, and tender shoots of grasses, I am informed

by a Quail-shooter that the flesh of the Ground~Parrot is excellent

eating, and equal to that of Quail.

The breeding period ranges through the months of September,

October, and November. The eggs usually number three or four

to a clutch, are round in form like most Parrots’ eggs, and of a

glossy white colour, with a shell of fine texture. It is somewhat

remarkable that the eggs are not coloured, like those of most

ground-nesting birds. Coloured eggs afford some modicum of

protection from the prying eye of an enemy. This fact is all the

more noticeable when we know that the nest of the Ground-

Parrot is simply a somewhat deep hollow in the ground. The nest,

which is composed of grasses, is placed in a grass tussock or in

a mixture of heath and coarse grass, which, overlapping as a

rule, forms an overhead canopy.

Three varieties or sub-species of the Ground-Parrot are

recorded for Australasia, viz. :— P. formosus, (Latham) - range,

South Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia;

P. flaviventris, (North) — range, Western Australia; P. leachi,

(Mathews) — range, Tasmania.

'

*Little seems to be recorded with reference to the immature plumage of

Pezoporus. The red patch on the forehead is missing in the immature birds

during their infancy, but is represented as they develop by a small dull yellow

patch, visible in both sexes. The plumage of the ventral surface generally is

more suffused with yellow, whilst the dark marking of the feathers of the

throat is much more pronounced.